When done right, brand building delivers more long-term sales and profit than any other marketing communications tactic in our arsenal. It's not even close.

But what does "brand" even mean, anyways?

Better yet, what type of brand should we be building? And how do we build one?

In this chapter, we'll explore the varying degrees of brand, a proper definition for the one you need to build, and the fundamental principles underpinning effective brand building.

- What is brand building?

- What brand building is NOT

- The path to sustainable growth: why brands need building

- How to build a brand: Growing mental availability

- 1. Expand your buying pool

- 2. Broaden your message

- 3. Sow the seeds of emotion

- 4. Be meaninglessly distinct

- 6. Play the long game

- Brand building traps

- How to measure brand building: leading and lagging indicators

- Wrapping up

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for tips so good that we might put ourselves out of business.

What is brand building?

Ask 100 marketers what brand building means, get 100 different answers.

That’s because the word “brand” is a shifty shapeshifter: it can mean different things in different contexts.

For example, take the following definitions of brand (all acceptable):

- Brand (verb): To mark your products and communications with distinct codes (as cattle brand or branding)

- Brand (noun): A person, business, or thing (podcast, series, book, etc.) with a unique identity (as in “being your own brand”)

- Brand (noun): A business that has reached the top of their category, as opposed to a non-brand that hasn't.

- Brand (noun): A product made by a specific business under a unique name, like a new brand of deodorant from Old Spice.

- Brand (noun): A particular type of something, as in a “dark brand of comedy.”

- Brand (noun): The name of an actual business.

Confused yet? There’s more…

Then you have your brand platitudes, like “brand is your reputation,” “brand is demand,” “brand is the sum total of all the experiences a customer has with your business” and, my favorite piece of drivel, “brand is everyone’s responsibility.”

Any way you slice it, 90% of marketing can’t seem to agree on what type of brand we’re supposed to be building. And that’s exactly why the brand “can'' keeps getting kicked down the road (and sustainable growth remains forever fleeting).

The truth: It’s time we cast aside the abstract, generic definitions of brand in favor of a more practical, instructive definition that implies a certain set of activities needed to build one.

To do that, we need to work backwards.

If we want to know how to build a brand, then what does the science (Sharp, Romoniuk, Binet, Fields, Et al.) say an ideal brand looks like once it’s been built?

Simple: One that comes to mind easily in a buying situation when a potential buyer first thinks about who can solve their problem or satisfy their need.

That’s it.

Definition: A brand is the business that someone easily thinks of or notices in a buying situation.

Not because they clicked on a direct response ad.

Not because a friend gave them a referral.

Not because they searched on Google.

But because the buyer already knew they existed and recalled them from memory when they were ready to buy.

Therefore, brand building is the practice of creating long-lasting memories in the minds of future buyers before they ever enter the market for what you sell.

The goal?

To increase the probability that someone will recall you when they’re ready to buy.

Or in financial terms, the purpose of brand building is to create future demand, cash flow, and profit by expanding the amount of people who will know, trust, and consider you in the future.

Simple enough, right?

Brand = the business that comes to mind or gets noticed easily in a relevant buying situation.

Brand building = the practice of reaching and influencing future buyers before they enter the market so that they remember you when they enter. Brand building is memory building.

Now purge the other definitions of “brand” from your lexicon.

We love them (not really). Ok, they have their place. But they’re distractions.

They don’t align with the science, nor do they imply a set of activities needed to build one.

But because there’s a good chance that a few lingering but popular half-truths live rent free in your mind, we’re actually going to help you purge them together.

Starting now.

What brand building is NOT

Let’s be honest: the brand train fell off the tracks a long time ago.

We’d be remiss not to explore the different forks that splintered our thinking over the last few decades while attempting to write a chapter on building a brand.

So that’s exactly what we’re going to do: talk about what brand building is not.

Up first: brand is NOT branding.

Brand is not branding

Branding dates back thousands of years to a time when farmers, potters, and traders from ancient Egypt and Rome would brand (as in cattle brand) their goods to prevent thievery, distinguish ownership, and signal quality.

Fast forward thousands of years and nothing much has changed.

In marketing, we use brand as a verb (or branding) to describe the action of placing labels, logos, and distinct codes on our products and communications to help customers notice, recognize, remember, and distinguish us from our competitors.

For example, one of the most famous brands of all time is Louis Vutton’s monogram pattern.

Other famous brands include UPS’ brown, Geico’s caveman, KlientBoost’s characters, Apple's power up sound, or Coca Cola's bottle shape.

While the branding team (or creative team) plays a critical role in helping your business stand out and be remembered (more on this later), namely with their stewardship of its distinctive assets (sounds, packaging, colors, characters, styles, etc.), they don’t own who sees it, at what moment, and for what reason.

They can visualize your brand, but they can’t build it. Not alone.

Which is why branding is not the same as brand or brand building. It’s just one piece of it, albeit an important one.

Brand building is not demand generation

Brand ≠ Demand.

Both brand building and demand generation work to accelerate demand, but two very different types of demand.

The brand needs to generate demand for the business, irrespective of its products or services.

The demand needs to accelerate interest for the business’ products or services.

The former is your brand positioning, the latter is your product positioning(s).

Big difference.

Two different approaches. Two different target audiences. Two wildly different sets of tactics needed to accomplish both.

We’ll dive deeper into brand vs. demand in the next chapter, and tell you why “demand acceleration” is a more accurate name than “demand generation.”

Brand building is not everyone’s responsibility

Before you cut my head off, let me just say that yes, we do believe that every encounter a potential or existing customer has with your business is an opportunity to strengthen (or weaken) your brand.

In that respect, brand building really does touch every corner of your business, not just marketing.

Heck, even performance marketing campaigns have been proven to increase brand lift and recall over time.

But if everyone owns brand building, then no one owns brand building.

So for purposes of action, best to give ownership of brand building to the marketing department. It’s not customer services’ job to build the brand, no matter how much their work leads to affinity, referrals, retention, or upsells.

The minute you resign to thinking that brand is the sum of the experiences someone has with your business is the minute it never gets the investment it needs to grow.

Brand is not reputation

It’s popular to use brand synonymously with reputation.

A better question is, “Reputation for what?”

- Delivering a superior product?

- Keeping your data private?

- Giving back to the community?

- Being nice to your employees?

- All of the above?

Not all reputations are created equal.

If your product or service solves a problem or satisfies a need better than others, it’s actually really hard to screw up your reputation in a way that costs you customers.

For example, if the strength of your brand relied on the strength of your reputation, then would the following brands still be on the fortune 100-1000 list?

- Monsanto

- Wells Fargo

- NFL

- Comcast

- Equifax

- Uber

- Spirit Airlines

Not a chance.

We still login to Meta products.

We still bank with Wells Fargo.

We still watch football.

And we still hail Ubers.

As long as your reputation for delivering a superior product/service that people want and need doesn’t suffer, buyers often give businesses a pass on all other aspects of business. That’s why businesses with track records of poor ethics but high demand still thrive (looking at you, Apple). Unfortunate, but true.

Apple has one of the strongest brands in the world.

So strong its customers look right passed their unethical treatment of overseas employees (child labor, sweat shops, unlivable wages, deaths).

Too big to fail? Perhaps.

But the truth remains: No matter how much your reputation helps maintain, build, or damage your brand, it’s still too nebulous to serve as a northstar.

Who owns reputation? How do you build it? How long does it take? Where’s the evidence?

We’re not suggesting that you disregard your reputation or participate in unethical business practices.

Nor are we suggesting that your reputation for delivering a superior product doesn’t help you build a strong brand. That’s a given and a must.

But reputation alone is not a functional or instructive definition of brand.

Brand is not what people say when you leave the room

To be clear, we’re not disputing that your brand isn’t a complicated amalgamation of associations and feelings. Nor do we disagree that your customers’ sentiment can illuminate the health of your brand, for better or worse.

But these, along with your reputation, are outputs, not inputs.

To build a brand people love, respect, and feel strongly about, first they need to know you exist, trust you can deliver, and associate you with what you sell.

Using customer sentiment as a definition for “brand” tells us nothing about how to build one.

Again, it’s too abstract.

Catchy. But abstract.

So we’re casting it aside. Sorry, Bezos.

The path to sustainable growth: why brands need building

Now you know what type of brand needs building.

But why do brands need building in the first place?

For many businesses, brand building has always felt like a luxury, not a necessity; a nice-to-have, not a need-to-have.

We get it: So many marketing departments are so chronically undercapitalized that they can’t invest in a future beyond a few months away. Not without going out of business.

But that doesn’t change one simple fact: The secret to long-term, sustainable growth isn’t more sales today; it’s a stronger brand tomorrow.

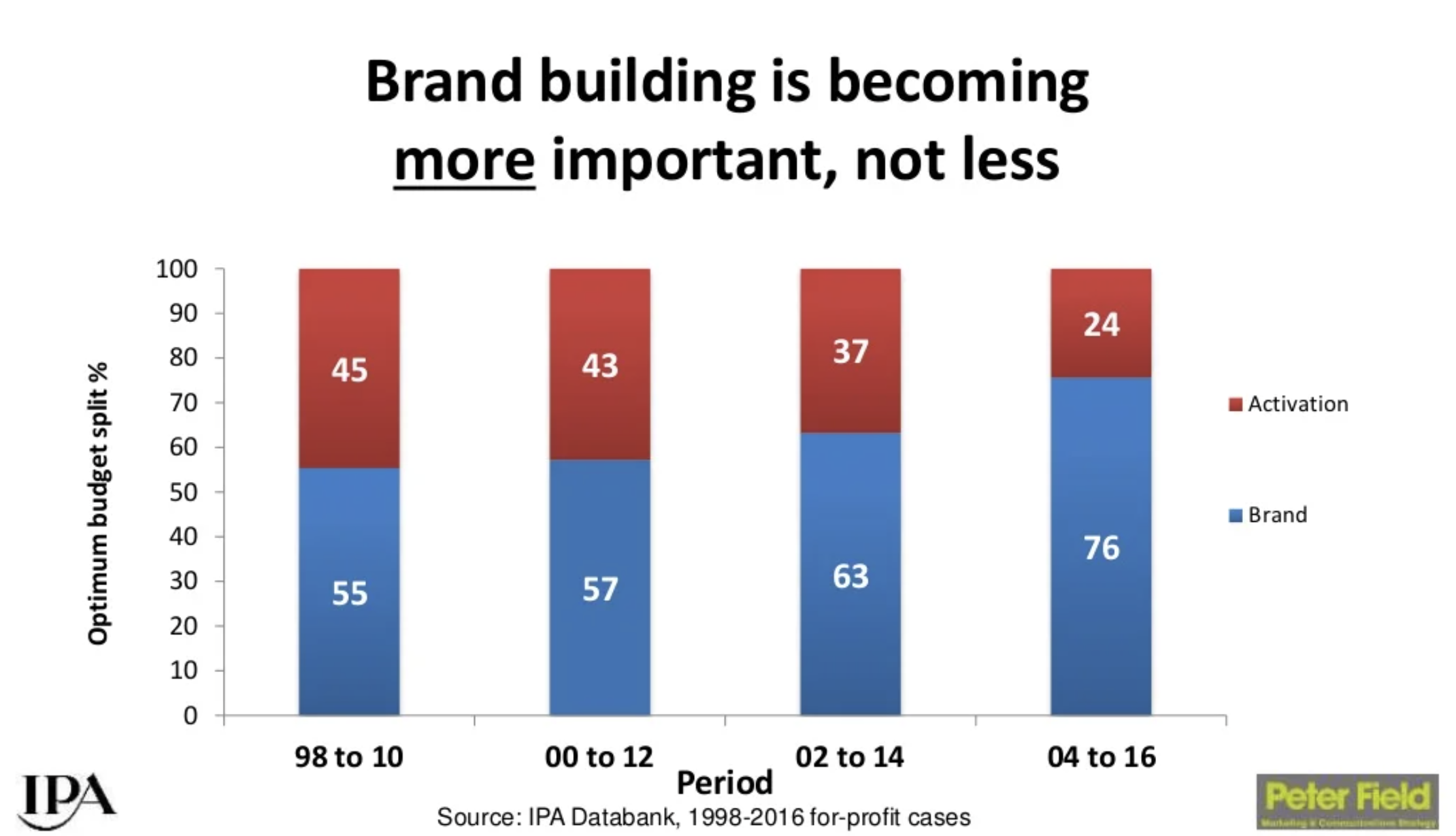

And the need for brand building is only getting more important, not less:

Why?

Because it’s never been easier to sell something or buy something online, no matter the industry.

And when capturing existing demand gets easier, that means you can spend less on it (though that’s not the lesson most marketers take away).

Consequently, the battle wages between brands. And the strongest ones win.

So how does brand building help deliver sustainable growth?

- Increase in base sales

- Deeper market penetration (market share)

- Reduced price sensitivity and more pricing power

- More absolute profit and cashflow

- Increase efficiency (short and long)

1. More base sales long term

The important distinction is that brand building and sales activation work over two different speeds: fast and slow. (We’ll explain where demand sits in the next chapter.)

Activation captures immediate demand, profit, and cash flow by targeting in-market buyers.

Brand building creates future demand, profit, and cash flow by targeting out-market buyers.

You can sustain growth for a time with always-on performance marketing targeted at in-market buyers (capturing demand), but, eventually, you’ll exhaust the active market and need to look to the passive market for growth.

Enter: base sales.

Whereas activation delivers short-term sales prompted by specific marketing activity, brand building increases base sales long term: sales that come through your door unprompted by marketing.

Think of base sales as being driven by mental availability, not an offer or call-to-action.

For example, remove promotions, direct response campaigns, sales outreach, seasonal campaigns, and other short-term marketing activity, and what do you get? Base sales.

If you only market to in-market buyers, the minute you turn off or pull back, a sales valley is inevitable. Which is why economic recessions hamstring so many businesses: they don’t have the brand cache to float sales if short-term spend decreases.

When strong brands turn off short-term activity though, they’ll continue to experience a flow of new business directly attributable to the brand alone. Those are base sales.

Deeper market penetration (market share)

Market penetration refers to the percentage of your total addressable market (TAM) that you sell to during a given time period.

Market share refers to the portion of your market’s total value that your business commands.

When you sell to more of your TAM (penetration), you increase your market share. Simple.

According to research from Binet and Fields, penetration is the main driver of very large business effects: sales, market share, price sensitivity, loyalty, and profit.

Supplying more of your TAM with products/services they demand (physical availability) is the single most important thing you can do to penetrate your market deeper. And we’ll cover that in the next chapter.

But brand building is the vessel that takes you deeper into your TAM before you have the products/services to sell there.

In other words, brand building creates mental availability with all category buyers so your physical availability can close the deal.

More pricing power (reduce price sensitivity)

When buyers know, trust, and consider you in advance of purchase, they pay more for even functionally identical products or services.

And we have the data: Stronger brands decrease price sensitivity in their buyers, command higher margins, and become more resilient to competitive pricing in the market.

More absolute profit and cashflow

When you can reduce price sensitivity, stave off price wars, and confidently raise prices, the reward is more absolute profit and cashflow.

And don’t let ROI fool you: it’s an efficiency metric, not an effectiveness metric.

ROI can tell you how efficiently you’ve converted $1 into many, but it can't tell you whether or not that was effective for your marketing. At all.

Efficient ≠ effective.

For example, want to increase ROI?

Super easy:

- Target in-market buyers or existing customers (easiest/quickest/cheapest to convert)

- Reduce ad spend (more spend = lower ROI usually)

- Only advertise in season (spend when it's hot, not when it's not)

- Avoid the top of the funnel like the plague (too far from purchase)

Works. Every. Time.

Then watch as you go out of business for:

- Failing to reach and influence out-market buyers

- Not spending enough money (you can't save your way to growth)

- Over-investing in upselling and retention (growth comes from acquisition, not retention)

- Never expanding your buying pool or growing base sales

While long-term brand building will reduce ROI (it’s supposed to), it will increase profit growth.

Short-term and long-term efficiency

Brand building seduces a bigger pool of potential buyers to your brand in a way short-term activity never will, making your marketing more efficient over the long term.

But brand building also increases short-term efficiency by increasing the number of in-market buyers who already consider you.

Brand makes everything that follows work harder.

How to build a brand: Growing mental availability

Remember how we worked backwards to find a definition of the brand you need to build?

Well, the roadmap to building a brand hides within that same definition (hence the reason for working backwards).

Brand = The business that comes to mind or gets noticed easily in a relevant buying situation.

Brand building = The practice of reaching and influencing future buyers before they enter the market so that they remember you when they enter.

Everything you do when it comes to brand building should work to produce memories and maximize mental availability. Period.

What’s mental availability?

“A brand’s mental availability refers to the probability that a buyer will notice, recognize and/or think of a brand in buying situations. It depends on the quality and quantity of memory structures related to the brand.” - Byron Sharp

When Bryon Sharp first introduced the concept of mental availability, he did so to expose a flaw with “awareness.”

For example, if you’re Coca Cola, it’s one thing to get your name mentioned when you ask someone to name a brand in the soda category (awareness). It’s another thing entirely to get your name mentioned when asking someone to name their drink of choice for a hot summer day (availability).

Context matters when it comes to awareness.

You don’t want people just to associate you with your category when prompted, even if you're the first brand to mind. You want them to remember you during relevant buying situations.

So how do you maximize mental availability?

How do you become more salient?

And with whom are you supposed to grow share of mind?

Brand building in seven steps:

- Expand your buying pool

- Broaden your message

- Sow the seeds of emotion

- Be meaninglessly distinct

- Play the long game

1. Expand your buying pool

Unlike with sales activation or demand acceleration, reach (as in reaching as many category buyers as possible) trumps targeting when it comes to brand building.

To be clear, when we say “reach,” we’re talking about reach relative to your size: as your business and sales goals get bigger, your need for reach gets bigger too (unless you want sales to decline).

Why is reach so important?

Simple: Marketing only works when people see it. And most people don’t know you exist.

It’s brand building’s job to sell deeper into the market- all of it.

Think about it: Long-term growth comes from expanding your buying pool over time. That means selling to more of your total addressable market (TAM) than you do right now. Brand plants your flags in the places you're going to be tomorrow, so that when you get there, buyers already know, trust, and consider you.

So how do you expand your buying pool?

Three ways:

- Reach all category buyers, not just certain segments

- Reach out-market buyers, not just in-market buyers

- Reach your future market, not just your existing market

Let’s start with the first: all category buyers.

Reach all category buyers, not just certain segments

For decades, disciples of the Al Ries/Jack Trout school of positioning were taught that tight targeting and “owning a niche” was the secret to differentiation, and that differentiation through narrow positioning was the secret to limiting your number of competitors.

I was one of them.

To do that, you had to carefully segment your market into homogeneous groups, then target a specific segment with a specific position (since different segments had different needs and wants), then ignore the other segments altogether.

“The riches are in the niches!”

Fast forward three decades and it turns out meaningful differentiation through tight positioning is much less effective than we thought.

Why?

First, people buy across segments all the time (Hammond, Ehrenberg, Goodhardt, 1996), and competing brands within a category share remarkably similar customers, despite their positioning.

It’s called the Duplication of Purchase Law: Buyers share customers with all category competitors proportionate to their market share.

For example, in both B2B and B2C, brands share more customers with the largest brand in the category and fewer customers with the smallest brand in the category, despite positioning.

That means that Klaviyo (email for ecommerce), ConvertKit (email for creators), and SendInBlue (email for high volume) will lose most of their churned customers to the market leader, MailChimp (email for everyone), despite their niche focus.

That also means that buyers don’t perceive niches like we do. Otherwise they wouldn’t buy across them.

Second, if differentiation through segmentation were so effective, don’t you think loyalty would be much higher for differentiated brands?

If segments were so homogenized, and if buyers within those homogenized segments only bought the brands positioned for their segment, you would expect smaller customer bases with much higher loyalty, right?

But that’s not what happens.

Though loyalty does exist (more for subscription brands, less for repertoire brands), levels of loyalty do not vary much from one brand to the next, with the exception of one factor: size.

It’s called The Law of Double Jeopardy: The biggest brands have the most loyalty; the smallest brands have the least loyalty (smaller brands lose twice).

Turns out loyalty has more to do with acquisition than tight positioning.

Last, marketers put buyers into segments; they don’t put themselves into segments.

Which is why buyers rarely perceive differences like we do, and why you’ll often find your customers are not the ones you expected.

For example, notice how buyers perceive computer brands (even Apple) largely as undifferentiated or not unique?

And notice how consumers rate different brand attributes relatively the same even when those brands come from wildly different categories?

It’s not that meaningful differentiation isn’t real. Nor are we suggesting that understanding your market is pointless or that you shouldn’t meet the needs of different partitions when they appear.

But the truth remains: Real sub-markets don’t exist like we think, buyers don’t perceive differences like we want them to, and customers buy across segments all the time despite positioning.

Instead of “owning” a segment or “niching down,” better to target all segments within the category that have a problem you can solve or need you can satisfy.

When real partitions present themselves (they always do), find ways to serve those partitions with functional additions to your product/service or tailored messaging here and there.

Just don’t think that you need to narrow your focus to reduce competitors and grow, because that’s not how this works. Narrowly targeting a segment with a focused position does not actually limit competition as we showed; it only limits growth.

Last, “all category buyers” does not mean everyone in the world.

It just means targeting all segments within the market that you sell to, not some of them.

And that doesn't mean targeting them all at once either; it just means setting your long-term sight on the market, not the segments within it.

Reach out-market buyers, not just in-market buyers

The amount of people actively seeking products or services you offer at any given moment pales in comparison to the number of people who will become customers of your category in the future. It’s not even close.

It’s called the 95:5 Rule, established by John Dawes from the Ehrenberg Bass Institute of Marketing Science.

The 95:5 Rule is a heuristic, not a precise rule (i.e. it could be 99:1 or 90:10 depending on your industry), stating that at any given moment, the vast majority of people (95%) who encounter your marketing are not in-market for any good or service.

In fact, only 5% of people who will ever consume your media are actually looking to buy what you sell right now.

Seems obvious, right?

What’s not so obvious is that if only 5% of your market is actively seeking what you sell, then there’s also a low ceiling on how much growth you can capture by marketing to them.

As you spend more and more money chasing today's buyers, and as more and more competitors enter the market who do the same, less and less available demand remains to capture.

Sure, you can sustain growth for a time by just marketing to in-market buyers- and you should.

How long that growth keeps moving “up and to the right” will depend on your industry, competition, budget, and sales goals.

But eventually, as sales goals get bigger, competition gets heavier, existing demand gets gobbled up, and your pool of in-market buyers starts to shrink, there's only one way to stave off a sales plateau: to expand your buying pool by reaching and influencing tomorrow's buyers today.

By creating lasting memories with an expanding pool of future buyers, brand building increases the amount of people who will consider you when they go in-market tomorrow.

The results? Future demand, future profit, and future cash flow.

Given the lopsided numbers (95-5), reaching and influencing a fraction of out-market buyers can produce a greater impact on sales tomorrow than in-market buyers can impact sales today.

So while it’s tempting to home in on prospects with the highest likelihood to convert at the highest ROI (i.e. in-market buyers), reaching and influencing future buyers before they have the problems you can solve is what grows base sales long term.

Reach your future market, not just your existing market

It’s impossible to know who will enter into your market in the future.

For example, how does Mercedes know who will enter the market for a luxury car in the future?

How does Anheuser Busch know who will enter the market for a beer in the future?

Or how do we (KlientBoost) know which marketers will work their way into future businesses or leadership roles where they’ll have the authority to choose a marketing agency?

We don’t.

Which is why effective brand building generates availability with people who might potentially enter the market in the future but who aren’t within that target market yet.

- They might not work at the businesses you serve yet.

- They might not sit in the positions that can make a purchase decision yet.

- They might not fit the age requirements to buy what you sell yet.

- They might not have the symptoms for your diagnosis yet.

- Or they might not have the disposable income to afford your product yet.

But they all might in the future.

The strongest brands zoom out: Instead of obsessing over ICPs, SAMs, or TAMs (i.e. the markets that you sell to today or the people that you know can buy today), they target their brand building activity toward a broad audience of all potential category buyers.

And, yes, even if that means some of those people will never enter the market for what they sell or, if they do, never buy from them.

Zooming out doesn’t mean target everyone in the world.

For mass-market brands like Mercedes or Anheuser Busch, it kind of does. That’s because their future market is so massively broad, so they run brand ads to kids as young as 10.

But for us at KlientBoost, zooming out means reaching for the broadest group of people who might need to solve the problems we can solve in the future: all marketers.

Marketing isn’t just about finding the customers you already know exist; it’s about finding who else exists that you don’t know about.

Which is why the hallmark of effective brand building will always be simple ideas with broad, universal relevance.

2. Broaden your message

Out-market buyers. All category segments you sell to. Future market.

That’s a big, broad net to cast.

Not to mention most of those potential buyers won’t have a problem you can solve any time soon (perhaps never).

How do you resonate with all of them in a way they’ll remember?

Big ideas with universal relevance.

When it comes to brand building, unlike demand or activation, the most effective (and efficient) message is the one that resonates with everyone, even those who aren’t interested in buying right now.

I know what you’re thinking: “I thought the only way to broaden our appeal was to narrow our focus?”

There’s this misconception that hyper-targeted messages perform better. Just like the misconception that hyper-targeting segments reduces competition.

True, hyper-targeted messages are more relevant.

But so what?

Relevance is a spectrum, and you don’t need to be on the “hyper” end of it.

If Disney can resonate with every race, gender, orientation, ethnicity, age, income, belief, value, or political affiliation, you can spin a universal narrative that resonates with all category buyers.

It’s brand building’s job to find the thread connecting everyone, then communicate that message in the most distinct and memorable way possible.

You can’t do that efficiently or effectively with dozens of disparate messages targeted at different parts of the market. But you can with a broad, universal message for everyone.

What does universal relevance look like in practice:

- Category entry points (CEPS), not pitch slaps

- Market education, not pitch slaps

Category entry points, not pitch slaps

Product-oriented information is only relevant for in-market buyers from your serviceable market (i.e. people who currently have the problems you solve and want to solve them now).

But what about out-market buyers or future category members who don’t have a problem you can solve yet?

What good does product messaging or offers do for them?

Not a whole lot.

In fact, most out-market buyers will gloss right over product messages and never remember them again (rational messages have a fast decay).

Which makes product/service messages and offers inherently targeted, not universal.

Therefore, when it comes to brand building, the focus shouldn’t be on selling your products or services; it should be on linking your brand to the buying situations in which one might need one of those products or services.

Big difference.

We call those buying situations category entry points (CEPs), introduced by Jenni Romaniuk and the Ehrenberg Bass Institute of Marketing Science.

“Category Entry Points (CEPs) are the cues that buyers use to access their memories when faced with a buying situation, and can include any internal cues (e.g., motives, emotions) and external cues (e.g., location, time of day) that affect any buying situation.”

- Jenni Romaniuk

Think of CEPs like triggers: Buyers reference their memory at the start of every buying process. CEPs represent the situations and needs that trigger those memories at the category level.

Key word: category.

Brand building should associate your brand with your broad category and its most important buying situations, not your individual products and their features.

For example, notice how Salesforce uses the below ad to link their brand to a handful of relevant buying situations without ever showing the product: marketing and sales alignment, IT and business alignment, customer and service alignment, and company and customer alignment.

Or notice how Geico never explores their 30+ types of insurance but instead links themselves to the broad category of insurance (and “hump day”):

Unlike products and services, CEPs are universally relevant.

That’s because they’re about the buyer and their potential problems, not the product or your potential solutions.

We can all identify with future problems that might need a solution, even if we haven’t experienced those problems yet.

But we only identify with the features and benefits of that solution when we’re looking to buy.

Plus, CEPs are a better way to approach positioning.

Whereas old school positioning (Ries/Trout) asked marketers to posit, “What can we own outright in the mind’s of our buyers that’s different from our competitors?” CEPs ask us to posit, “How can we get buyers to think of us in as many relevant buying situations that matter?

People don’t spend their waking hours thinking and comparing brands or organizing their differentiated attributes like rungs on a ladder. Only marketers do that.

But they do spend their time asking questions like:

- "What will I eat for dinner in this hot weather?"

- "What can help me stay awake?"

- "How can I meet my deadline on time?"

- "What will help me get promoted?"

- "What can I bring to my company party?"

- "What can I do to treat myself?"

- "How can I integrate more of my tech stack?"

Therefore, it’s less important that buyers think of you in the right way, and more important that they think of you at the right time.

And not just one right time, but as many buying situations as possible.

The biggest brands have the most CEPs links:

Also, according to research from Jenni Romaniuk and LinkedIn, the more CEPs people link to your brand, the lower their probability of defection (switching brands).

So what do CEPs look like? And how do you choose them?

CEPs come in seven types:

- How (emotions): Feel more confident, reduce stress, help others be happier

- Why (motives/benefits): Increase productivity, get a promotion, lose weight, look younger

- When (timing issues): Morning vs. night, summer vs. winter, hot vs. cold, now vs. later

- While (co-activities): Launching a new product, sleeping, in a meeting, while running

- Where (location): At home, in office, on vacation, at beach, in another country

- With/for whom (other people): Manager approved, buying committee, friends, teammates

- With what (co-purchased): CRM integration, HIPAA compliance, SPF, roadside assistance

According to Ramoniuk, when choosing CEPs, look for three criteria:

- Credible: Does the buying situation fit within your perceived (by the market) product range?

- Competitive: Is the buying situation ultra-competitive? Or can you stand out?

- Commonality: Does the buying situation occur frequently? Or rarely?

Market education, not pitch slaps

For the large majority of brands, both B2B and B2C, market education is their entire brand strategy.

Why?

Online.

Most of the people reading this will never have the budget to explore TV advertising, nor would it make sense even if they had it.

Instead, they rely on online media channels like social media, blogs or websites, podcasts, YouTube, online communities or groups, and forums to reach category buyers and grow mental availability.

None of those channels will earn you attention without delivering something the market values: education or entertainment (usually both).

So in order for most brands to build a brand, they need to educate their market.

And what better way to educate your market than by helping future and potential buyers diagnose problems you solve, then giving them the tools to solve those problems on their own?

Not only does that approach give you the sustenance to scale different channels and reach more category buyers, but it also sets buyers on the path toward investigating your products and associates your brand with relevant buying situations.

Win win.

P.S. We call this BrandGen, and we’ll explore it in the next chapter.

3. Sow the seeds of emotion

By now, one thing should be clear: brand building is ostensibly about seducing people to your brand well in advance of purchase.

To do that, not only do you need a universal message that people will resonate with even when they’re not buying, but you also need to make that message memorable.

Enter: emotion.

To be clear: When we say emotion, we’re not talking about moving people to tears (though that can work too); we’re talking about making potential buyers feel positive about your brand in an effortless way.

Make people laugh. Tug at their heart strings. Empathize with their fears. Normalize their insecurities.

Emotion does two things well that make it a powerful ingredient for brand building:

- Memory

- Preference

First, emotions speak to our “System 1” brain, which is unconscious, fast, and effortless, and it’s the main source of the explicit beliefs and deliberate choices we make later.

Rational, persuasive messages (“System 2”) decay in the mind much quicker than emotional ones. But emotions have the power to create memories and feelings that influence sales for years to come.

Second, brand building needs to do more than just get buyers to remember you when they go in-market; it also needs to get them to prefer you.

No amount of product messaging will increase preference for someone who has no interest in buying.

Emotions, on the other hand, have the power to engage non-buyers in a way that makes them feel emotionally closer to you, which, in turn, positively influences their deliberate choices when they’re ready to buy.

The results speak for themselves: Based on data from IPA, emotional campaigns produce the largest business effects (sales, profit, revenue, market share, loyalty) in the long run- by a lot.

But what about B2B?

Surely, given the nature of B2B decisions (buying committees, long sales cycles, high price tags), emotion must take a backseat to rationality, right?

Not really.

Turns out rational consideration is only slightly more important in B2B than it is in B2C:

And just like in B2C, emotional campaigns outperform rational ones when it comes to long-term brand building:

Bottom line: Whether B2B or B2C, emotionally priming your future buyers builds a bridge between consideration and preference.

4. Be meaninglessly distinct

Distinctiveness in marketing means looking and sounding like you and no one else so that buyers can easily identify you without confusion.

When people see your brand and its marketing, do they immediately recognize it as yours?

What if you removed your logo?

What if they closed their eyes and read aloud?

What if they could only feel your packaging?

Would they still know it was you?

Probably not. And that’s a problem.

According to LinkedIn, half of brands today get mistaken for competitors. Yikes!

To ensure that your brand building activity generates sales for you and not a competitor who looks like you, grow a collection of unique and distinct brand assets.

- Brand characters: Salesforce mascot, KlientBoost characters, Budweiser frogs

- Sounds: PlayStation power on, Netflix power on, Slack message sent

- Shapes: Coca Cola bottle, RedBull can, McDonald’s arches

- Colors: UPS brown, Starbucks green, Hermes orange

- Themes: Geico caveman, AllState mayhem,

Distinct brand assets serve as “fluent devices,” or recurring creative devices used to create memorability over time.

Make no mistake: Distinct brand assets can increase brand recall, refresh memories, and influence sales.

According to Kantar, shapes, patterns, and logos are the most effective distinct assets for cueing brands:

When choosing distinct assets, shoot for unique and uncompetitive:

A note on distinctiveness in B2B

Why is B2B marketing so boring?

Aside from marketing by committee (which kills creativity), B2B marketing tries to jam too much meaning into every piece of marketing but not enough distinctiveness.

You know the story: features, benefits, outcomes, data, problems, solutions.

B2B marketers need to spend less time telling the rational, logical story of their products/services and more time making those stories distinct, unique, and memorable.

Logic is inherently boring.

For example, Geico sells home and auto insurance.

From a logic standpoint, that's about as boring as it gets.

But Geico advertising is anything but boring.

That's because they don't obsess over meaning; they obsess over distinctiveness- looking and sounding uniquely like themselves and no one else.

The caveman and gecko are two of the most meaninglessly distinct figures in all of advertising, ever. They’re also two of the most effective because everyone knows and remembers them.

Both serve as vessels: without them, we'd be left with a boring, rational story about insurance that we'd never remember.

This is where most B2B marketers find themselves: a striped down, rational message without a distinct and emotional vessel.

The result? Boring marketing.

And boring marketing = ineffective marketing.

If your marketing is boring, it's likely too rational and meaningful.

If it's too rational, it lacks emotion, which means it's not as memorable.

If it's not memorable, it's not effective.

The path to "unboring" your marketing starts with less meaning, more distinctiveness.

Less logic, more emotion.

More vessels, fewer features and benefits.

Stop trying to fill every piece of communication with meaning.

Instead, be meaninglessly distinct.

6. Play the long game

Brand building is a game of bigger but slower paybacks.

By reaching and influencing out-market buyers before they enter the market, brand building makes next year’s sales goal easier to hit, not next month’s.

To do that, it requires a commitment to consistency.

Yet here’s how a typical brand building program usually starts and ends:

Month 1: Launch creative brand campaign

Month 3: Tell each other how creative we are

Month 6: Wonder why it’s not working yet

Month 7: Recoup budget and put it back into short-term activation

Month 13: Repeat at step one.

All the time, brand effects weren’t given enough time to actualize, and you wasted money doing it.

In the short term (less than six months), activation will always look like they win. That’s because activation drives immediate sales from in-market buyers. But over the long term (6-12+ months), brand building outperforms.

Bottom line: Let it marinate.

Brand building traps

Traps, traps, everywhere.

When building a brand, beware of these boobie traps.

ROI

ROI is the most misleading metric in a marketer's toolbox.

Why?

It's an efficiency metric, not an effectiveness metric.

It can tell us how efficiently we've converted $1 into many, but it can't tell us whether or not that was effective for our marketing. At all.

Efficiency ≠ effective.

ROI by itself is a dangerous metric. And marketer's need to stop obsessing over it.

ROI obsession (often masked as attribution obsession) biases our action toward the bottom of the funnel.

As soon as we invest in longer-term brand activity, and as soon as ROI dips because of it (it's supposed to), we retreat back down the funnel. Because, ROI

But which campaign would you rather run?

Use ROI to track the performance efficiency of your direct response campaigns. It's great for DR campaigns since DR is designed for short-term, immediate action (ROI = short-term return divided by short-term cost, not long-term return divided by short-term cost).

But even still, what's included in the cost? Just ad spend? All marketing expenses? And what about the strength of your brand or other touch points? Does that not count for something?

For everything else, tread lightly.

By itself, and without context, ROI literally means nothing.

As marketer's, it's our job to deliver more absolute profit. To do that, we have to spend money building brand with the whole market, not just the part that delivers the highest ROI (the active market).

Which means step one should always be effectiveness, not efficiency. Because scaling ineffectiveness efficiently is a good way to go out of business.

Attribution

If ROI is the disease, attribution is the symptom.

Most brands will never have access to the type of sophisticated brand tracking, marketing mix modeling, or econometrics that big brands use to better measure the long-term success of their brand building efforts.

As a result, and because marketers and C-suite leaders love trackable ROI, this biases many businesses away from hard-to-measure brand activity.

But just because you can’t measure it precisely, doesn’t mean it’s not working.

For example, podcasts, social media, OOH, events, and sponsorships make up just a handful of sound brand building activities that you can’t easily track. But they all work.

We believe that the next decade in marketing will bring about more accessible and effective ways to measure long-term brand building for brands who can’t afford to spend millions of dollars doing it.

Until then, pay close attention to the leading and lagging metrics we outlined in this chapter to ensure your brand activity is doing its job. Then learn to live without granularity.

Brand target vs. media target

There’s a difference between targeting your media at a segment of the market and trying to differentiate your brand by positioning for a segment of the market.

Reaching the entire market isn’t cheap.

Good news: it’s not cheap for everyone. Which means you’ll likely never have the budget you want to reach all category buyers all the time.

But just because the goal is to target all category buyers, it doesn’t mean you need to start there, nor does it mean you have to narrowly describe your target market in a way that excludes other potential buyers.

Pay for as much reach as you can afford, even if that means a small portion of the market. Then grow your brand budget over time.

In the end, no matter where you start, the market will be your target, not the segments.

The Heavy Buyer Fallacy

Despite what many believe, most of a business’s sales growth will come from light or occasional buyers, not heavy buyers.

That means buyers who don’t buy your brand very often, or, when they do, they don’t spend much and they’re not your most profitable customers.

It’s called the Heavy Buyer Fallacy: First discovered by Andrew Ehrenberg in 1959 and since expanded upon by Byron Sharp, the Heavy Buyer’s Fallacy shows that a brand’s customer base follows a banana curve where about half of its sales come from light buyers.

Marketers like to target their heavy buyer behavioral segment in hopes that they can drive more loyalty and purchase from the people who already buy them.

This approach ignores the segment of the market with the most potential: light buyers.

Also, whereas heavy buyers already buy your brand often or spend more money when they do buy, it's your light buyers who have the potential to spend more, more often. Marketing actually works better on them.

Brand building does the work of getting light buyers to think of your brand more often in more buying situations. Don’t ignore them.

Community

At its core, community building delivers exceptionally high frequency to a small market (compared to your TAM).

One problem: frequency has diminishing returns.

A 12th impression does not have the same effect as the 1st impression (the "rule of three" is an old myth).

Which means community building has two glaring weaknesses:

- Excess frequency

- Limited reach

So the question remains: Are you spending your resources creating super fans, or are you spending them creating sustainable growth?

Community can deliver valuable benefits, despite its weaknesses: customer conversation, feedback, research, word of mouth, etc.

But as marketers, we have to be realistic about its potential.

Too often we get caught up measuring community KPIs but fail to ask ourselves whether or not that community is big enough to sustain growth in the first place.

Many times it's not.

Sure, if you're a content creator, solopreneur, small business with high annual contract value or a super long sales cycle, or any other business that doesn't require scale to grow, community makes more sense.

But even still, that same community that delivered early-stage growth isn't going to deliver the same growth as your sales goals swell over time. Not unless that community swells with it.

Not to mention that community often attracts the super fans of your industry, not the light buyers, light media consumers, or future buyers you need to sustain long-term growth.

This idea that brands need to keep attention long-term in order to build trust and affinity romanticizes the relationship marketing has with buyers.

It's fun and feels good, but it's overkill most of the time.

So before you build a community of 12th, 13h, 14th+ impressions, build a machine that creates more 1st impressions with more potential buyers.

How to measure brand building: leading and lagging indicators

What should we track to measure the performance of our brand building activity?

How will you know if you’re reaching and influencing future buyers so you can make next year’s sales goal easier to hit.

Even though most of you reading this won’t have access to sophisticated marketing mix modeling, brand tracking, or econometrics, that doesn’t mean you can’t measure the performance of your brand building activity.

Don’t aim for perfection. It doesn’t exist.

But a handful of leading and lagging indicators can help any brand determine whether or not their brand building activity is performing.

Brand building leading indicators

Keep it simple. Thankfully, when it comes to brand building, there’s tons of useful (and easy to measure) leading indicators at our disposal.

- Share of search: When you search Google Trends for your brand name (e.g. “KlientBoost”), then compare your search volume against your competitor’s brand names, how do you fare? Strong brands will see their share of search (i.e. brand name search volume) increase over time. And the strongest brand in the category will usually have the highest share of search amongst the group.

- Branded search volume (branded organic): When you check keyword queries in Google Search Console, strong brands will see an increase in the number of search queries that have their name in them (brand name, product names, leaders names, other brand IP names).

- Blended non-paid website traffic (branded organic, direct, referral): If brand building is working, aside from brand organic queries, you’ll also see an increase in direct traffic and referral traffic. How many people open a browser and type in your URL directly (direct traffic)? How many visitors come through other websites talking about you (referral traffic)? How many people come through brand organic? Aggregate and measure.

- Mental availability survey: Traditional aided or unaided awareness surveys fail to measure whether or not buyers think of you when it matters: in relevant buyer situations. But, as you know, the strongest brands get associated with the most category entry points. Instead of asking whether or not someone can think of your brand when they see your logo or think of your category, ask them who comes to mind for the buying situations you want to own.

- “How did you hear about us?” (self-reported attribution): No better way to discover who listens to your podcasts, follows you on social media, or subscribes to your media than by asking them at the point of sale. Good ol’ fashioned qualitative feedback.

Brand building lagging indicators: baseline sales

Good news: You don’t need an econometrician on staff to help measure brand’s impact on your bottom line.

Just measure baseline sales.

Baseline sales are the number of sales that come through your door organically, even with short-term marketing turned off.

For example, turn off promotions, direct response campaigns, sales outreach, temporary discounts, seasonal activity, and other short-term marketing activity, and what happens?

Most companies would say, “Go out of business.”

But when strong brands cut back on short-term marketing activity, they still experience a flow of new business directly attributable to the strength of the brand. Those are baseline sales.

To calculate baseline sales revenue, don't actually turn off short-term activity.

Instead, subtract the sales attributed to short-term marketing from the total sales for a period.

Strong brands should see a growth in baseline sales over time while reducing dependence on promotions.

Modeling baseline sales can get difficult and expensive the more sophisticated it gets.

So keep it simple.

It doesn't need to be perfect (it never will be); it needs to be consistent. And every business’s version of baseline sales will differ.

Just remember that the sales "attributed to marketing" doesn’t mean all of your marketing; it means the activity designed to influence immediate sales from in-market buyers:

- Promotions

- Discounts

- Seasonal factors

- Outbound sales

- Direct response (PPC)

- Purchase-intent SEO (revenue from in-market keyword rankings)

Timeframe

Though brand activity will lead to short-term sales, the goal is to make tomorrow’s sales goal easier to hit, not today’s.

Start tracking leading indicators immediately.

But don’t look for any significant change, especially in baseline sales, in less than a year.

In fact, annual (every 12 months) measurement is a perfect timeframe for measuring baseline sales growth.

And if you have a long sales cycle, that window gets even bigger.

For example, it wouldn’t make sense to measure the effects of your brand activity in less than 9 months if your sales cycle is 9 months. Not unless you think your brand activity is going to work immediately.

Wrapping up

A brand is the business that comes to mind easily in a buying situation (mental availability).

Brand building is the process of seducing future buyers to your brand in advance of purchase so they remember you when it matters.

Bottom line: The secret to long-term, sustainable growth isn’t more sales today; it’s a stronger brand tomorrow.

Strong brands penetrate their markets deeper, grow market share, increase base sales, reduce price sensitivity, increase profit, shorten sales cycles, reduce dependence on promotions, and increase retention.

But to do that, first you need to follow the five requisites of brand building:

- Expand your buying pool

- Broaden your message

- Sow the seeds of emotion

- Be meaninglessly distinct

- Play the long game

In today’s hyper-competitive world, brand is everything.

The best time to start building one was yesterday.

Chapter 4: Accelerating Demand: The Bridge Between Buyers & Revenue >>>